Here's a snippet from the beginning of the trip:

1:30 a.m., 1 June 1998

I’m

sitting in my room in the Hotel Višegrad, looking out onto the Drina and the

Turkish bridge, still lit by floodlamps. The bridge’s eleven arches are

reflected in the silky black river. A nightingale calls from across the river.

I’ve never heard a nightingale; but it can be nothing else. Unmistakable. It

calls again, and then again. It’s indescribably romantic. I’m alone in my room.

From

the terrace below there is an occasional burst of laughter from Peter, Zlatko,

Thomas, and Žarko, who are still talking with the two women from the Organization

for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the younger one from Spain, the older

from France. We argued for hours about the role of organizations like theirs in

Yugoslavia.

How

long have you been in Yugoslavia? Peter asked the French woman.

For a year-and-a-half, she answered.

Do you speak Serbo-Croatian? Peter

asked.

No, she answered. I’ve been too busy

to learn. The first town I was in was under attack for nine months. I worked

through an interpreter.

You are here to tell the people how

to run their country and you don’t understand their language! Peter exclaimed.

You can’t bother to learn their language?

Who are you? the woman asked. What

are you doing here? What gives you the moral right to judge what I’m doing?

Go home, Peter said.

Fuck you, the woman said.

Go home.

Fuck you.

The night air had chilled, and the

French woman was shivering. Peter took his coat from the back of his chair and

draped it around her shoulders. There, he said, that will help.

Fuck you, she said, and pulled the coat around herself.

A year later the trip continued:

6 June

1999, Vienna

In

the city center, I stumble onto a Sunday-evening demonstration against NATO and

for Yugoslavia. “NATO – fascistik, NATO – fascistik!” the crowd of maybe 2000

chants.

Back in my room, unable to sleep, I

turn back to my translation of Peter’s new play. I wish Žarko were here to

compare notes. How did he translate “Fertigsatzpisse”? Pissing your finished,

your modular sentences? Sentential piss?

At 10:30 I watch a report on Peter

done for Austrian TV (ÖRF2). Peter’s crime, the reporter and his commentators

agree, is that he is a “Serbenfreund,” a friend of the Serbs. Not good to be a

friend of the enemy. Peter should have known better, it’s an old story: Jap

lover, Kraut lover, Jew lover, Nigger lover, Serb lover.

I turn off the sentential piss and

return to Peter’s play. Before midnight I’m out of paper. I write across the face of my travel itinerary. I fill margins. By one a.m., having exhausted all possibilities, I look through the cupboards and drawers in my room. The drawer of the night table opens to a Gideon Bible, in the back of which are ten blank pages. I decide the hand of God has provided and rip them out and continue translating till first light.

9 June

1999, before midnight, Žarko's birthday, Vienna

I ought to go to bed, but I'm still

reeling from the events of the day.

Several hours ago NATO and the

Yugoslav Parliament came to some kind of agreement ending the bombing after 78

days.

And, I'm just back from the world

premiere of Peter's “The Play of the Film of the War,” directed by Claus

Peymann. I’ve seldom been this moved, this challenged, by a work of art.

The really bad guys of the play,

three “Internationals” who know all the answers, who dictate all the terms, who

can think only in absolutes, appear on the stage as follows: “Three

mountainbike riders, preceded by the sound of squealing brakes, burst through

the swinging door, covered with mud clear up to their helmets. They race

through the hall, between tables and chairs, perilously close to the people

sitting there.” American and European moralists, functionaries with no hint of

self-irony or humor, absolutists who run the world because of their economic

power – these sorry excuses for human beings were depicted this evening as

mountainbike riders.

“Žarko,” I said, “Don’t you ever tell

Peter I ride a mountainbike.”

“No,

my friend,” he whispered, “I’d never do that.”

The

play drew on several incidents from our trip, including when Peter put his coat

around the shoulders of the OSCE woman in Visegrad. After the play, flushed with

enthusiasm and insight, I told Peter how well he had integrated a real event

into an imaginative play. “Brilliant to put her and her friends on

mountainbikes!”

“Doktor Scott,” he chided, “Doktor Scott. Always on

duty.”

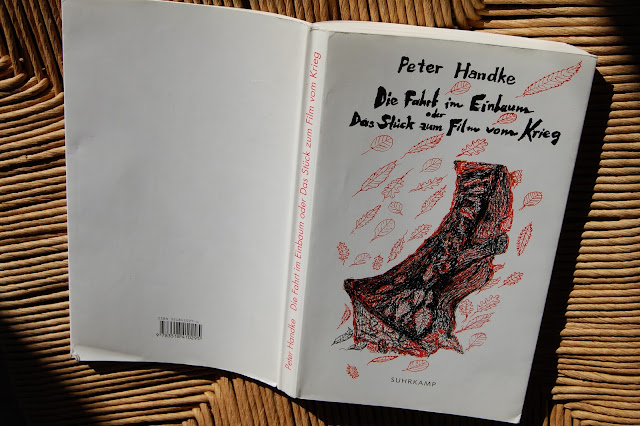

And now, thirteen years later, after trying 20 or 25 potential publishers, one of which backed out at the last minute out of fear of what Susan Sontag might think, I've just sent off the translation to PAJ, the Performing Arts Journal published by MIT Press. It will appear in May. Makes me happy, even as I and the book have seen better days.

3 comments:

congratulations on PAJ!

see scott, you'll get rich and famous.

but susan sontag is not in the position to complain anymore, no?

i do like the picture, i have a chair like that too.

there will be no rich and famous with this play. but it sure feels good that the translation will be published!

my youngest son Tim made the stool in his shop class and gave it to me. it's especially beautiful, i think, in morning sunlight.

Post a Comment